Summary: e all use different emoticons and symbols on social networks and in interaction with others daily to convey our message or feeling. But are these symbols, such as 😊or 😔, processed like real faces in the brain?

Do we need to take the virtual world more seriously in this regard?

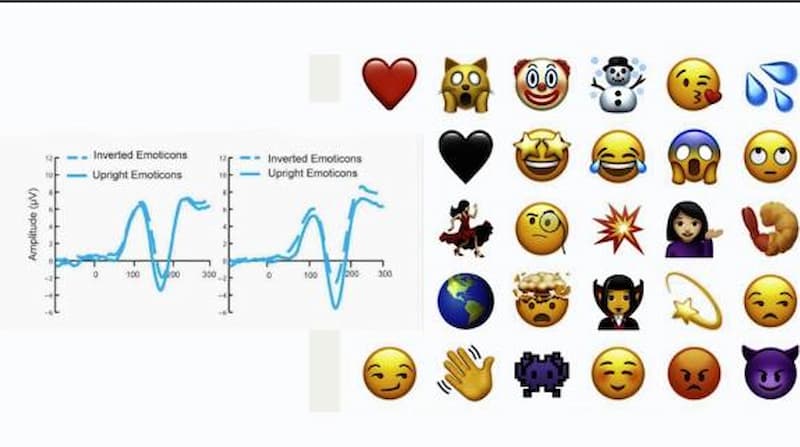

The results of a study using ERP on the use of a combination of symbols such as 😊 or 😔 used to represent smiling and sad faces have shown that our brain processes these symbols like faces. The process of decoding them takes place in the occipitotemporal region, but these are not the brain’s responses to these instinctual signs. In other words, a baby is not born with normal neuronal responses to these signs. Signs and symbols that we send or receive hundreds of items a day are likely to have a significant emotional impact on us and others. Social and the mysterious virtual world has become a part of our lives to be more aware of it.

Source:

Owen Churches1, Mike Nicholls1, Myra Thiessen2, Mark Kohler3, and Hannah Keage3

1Brain and Cognition Laboratory, School of Psychology, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

2School of Art, Architecture and Design, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

3Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, School of Psychology, Social Work and Social Policy,

University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

It is now common practice, in digital communication, to use the character combination

“:-)”, known as an emoticon, to indicate a smiling face. Although emoticons are readily interpreted as smiling faces, it is unclear whether emoticons trigger face-specific mechanisms or whether separate systems are utilized. A hallmark of face perception is the utilization of regions in the occipitotemporal cortex, which are sensitive to configural processing. We recorded the N170 event-related potential to investigate the way in which emoticons are perceived. Inverting faces produces a larger and later N170 while inverting objects which are perceived featurally rather than configurally reduces the amplitude of the N170. We presented 20 participants with images of upright and inverted faces, emoticons and meaningless strings of characters. Emoticons showed a large amplitude N170 when upright and a decrease in amplitude when inverted, the opposite pattern to that shown by faces. This indicates that when upright, emoticons are processed in occipitotemporal sites similarly to faces due to their familiar configuration. However, the characters which indicate the physiognomic features of emoticons are not recognized by the more laterally placed facial feature detection systems used in processing inverted

faces.